[ad_1]

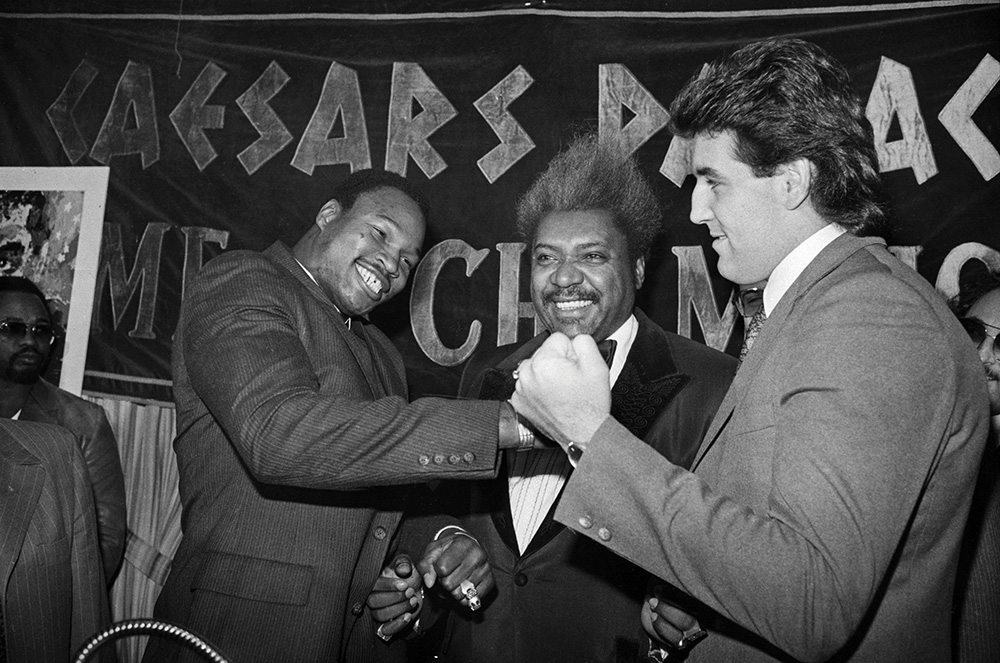

Gerry Cooney took his time before challenging heavyweight champ Larry Holmes. Here’s a brief moment of levity during an otherwise poisonous – and lengthy – buildup. Photo / Ring Magazine-Getty Images

The following article appears in the June/July issue of The Ring, on sale now at The Ring Shop. Subscribers can read the digital version here.

IT’S TAKEN YEARS FOR THE SPENCE-CRAWFORD SHOWDOWN TO HAPPEN, BUT DELAYED SUPERBOUTS ARE NOTHING NEW IN BOXING

If you’ve been irritated by the long stretch of time spent waiting for Errol Spence and Terence Crawford to get together, you aren’t alone. This year’s “big fight” fell apart more than once on the way to its forthcoming July date, and some in the business – not just the customers but actual card-carrying members of the so-called fight fraternity – have already sniffed with disdain about these two fighters, saying they should’ve fought years ago.

Well, maybe that’s true. But whether it was COVID-19 putting a damper on everything for a year or Spence enduring a car accident and then an eye injury, there always seemed to be something preventing this contest from taking place.

However, if the more impatient segment of fandom thinks Spence and Crawford have somehow wronged them, they should relax. Boxing politics being what they are in 2023, the oceans one must navigate in order to make a fight happen are not exactly smooth. Besides, this certainly isn’t the first time a pair of fighters took their time before agreeing to punch each other in the head for our amusement.

It was immediately after Sugar Ray Leonard had won the Ring and WBC welterweight titles from Wilfred Benitez in November 1979 when sportswriters began mentioning Thomas Hearns as a possible opponent for him. Hearns was undefeated and had soundly beaten journeyman Mike Colbert on the same night that Leonard won the title. Yet Angelo Dundee, Leonard’s cagy trainer and mentor, quickly put the brakes on any conversation concerning Hearns. Dundee had guided Leonard since the start of his professional career and knew a thing or two about the business. Dundee said something to the effect of, “Not right now. Let’s wait and let it get juicy.”

Leonard-Hearns I did not happen right away, but it delivered. (Photo by Focus on Sport/ Getty Images)

In other words, if the fight meant anything, it would still be meaningful a year or two in the future. Dundee knew a salient truth: Hearns wasn’t yet a household name.

Of course, boxing fans had been thinking about a Leonard-Hearns showdown prior to this, since both were young and dynamic welterweights. Then, as now, hardcore fans were always beating the drums for a fight long before it was realistically feasible, and long before casual fans gave a fig about it. In the meantime, Dundee had to hear the usual rubbish about how he and Leonard were frightened of Hearns and how Leonard was strictly a creation of the ABC-TV network. Fortunately, Dundee was a cool old head and kept a fight with Hearns percolating until it really meant something.

By the time Leonard and Hearns finally fought in September of 1981, it was one of the most lucrative contests of all time, an unprecedented blockbuster for a bout so far below the heavyweight class. Leonard won by TKO in the 14th. Dundee had been right to wait a bit. Big fights need a chance to simmer.

When Larry Holmes and Gerry Cooney stepped into a Las Vegas ring in the summer of 1982, it was the culmination of a nearly three-year gestation period. Cooney was an enormously popular Irish-American fighter from New York. A likable giant with a bone-crunching left hook and a charming smile, Cooney seemed to have been created out of the fantasies of old-time fight fans. As early as 1979, he was being mentioned as the next big star in the business, and Holmes was ready to fight him. But Cooney’s career had an erratic quality, largely because of personal problems that weren’t quite revealed until years later.

All we saw as we waited for Cooney to challenge Holmes for the heavyweight title was one delay after another. There were mysterious injuries and managerial issues and the pesky feeling that Cooney was stalling. Fans speculated that he was secretly scared of Holmes, too inexperienced or just plain not ready. He’d schedule tune-ups and then cancel them. By the time the fight happened, a bit of the luster had worn off. Yet Holmes-Cooney was a major moneymaker and, in the end, a competitive and entertaining fight. Holmes was too much of a sharpshooter for Cooney and stopped him at 2:52 of the 13th round.

Along with people casting their doubts about Cooney, the many delays brought out the racial components of the fight. Holmes often complained that the attention paid to Cooney was all due to his whiteness, which was partly true but not entirely. By fight night, extra security was set up around the arena in the advent of a race riot. Fortunately, nothing like that transpired, and Holmes and Cooney actually became friendly in the years after the bout. The bout’s racial elements, however, were nothing compared to a contest that took place on July 4, 1910, between Jack Johnson and Jim Jeffries, another bout that took forever to materialize.

Jeffries (left) un-retired after a year-and-a-half of public pressure to challenge Johnson. (Photo by PA Images via Getty Images)

Johnson was being mentioned as a possible challenger for Jeffries’ heavyweight title as far back as 1903, but big Jeff drew the “color line” and refused to defend the championship against Johnson or any other black contender. Jeffries retired, and Johnson was kept in limbo while Canada’s Tommy Burns claimed the title. But once Johnson yanked the laurels away from Burns in 1908, the public began clamoring for Jeffries to return from his retirement and bring the title back to the white race. There’d been well-liked black champions in the lighter divisions, but apparently having a black heavyweight champion was more than white supremacists could stand. Jeffries balked at first but eventually came back to face Johnson on a scalding hot afternoon in Reno. But the fight that had been talked about for seven or so years turned out to be a dull and one-sided anti-climax, with Johnson stopping Jeffries in the 15th.

Had Johnson-Jeffries been worth the wait? Not for those rooting for the white favorite. It may not have been worth it for Johnson, either, since he would only hear that he’d beaten a washed-up old guy who had been in retirement for five years. Even promoter Tex Rickard struggled in the bout’s aftermath; he’d hoped to make a big score on the fight films, but theaters wouldn’t show them for fear of inciting riots. Sometimes these long-awaited fights don’t pan out for anybody.

Jumping ahead 80 years, Mike Tyson was nearly Johnson’s equal as far as controversy. He also experienced some delays in making important fights happen. He was supposed to meet Evander Holyfield in 1990, but losing the heavyweight championship to Buster Douglas put the kibosh on that idea. Instead, Holyfield stepped in to fight Douglas and won the title. Tyson-Holyfield was eventually made for November of 1991. Unfortunately, a rib injury caused Tyson to request a postponement. This was followed by a rape conviction that landed Tyson in an Indiana prison for three years. While Tyson was getting accustomed to jailhouse cuisine, Holyfield’s career just about capsized. He dropped title bout decisions to Riddick Bowe and Michael Moorer and briefly retired because of health issues while Tyson was incarcerated, then lost his rubber match with Bowe shortly after Tyson’s release. He looked like a spent fighter even while halting undersized and overmatched Bobby Czyz.

Holyfield’s first shot at Tyson (left) happened five years after its original date. (Photo by Chris Farina/Corbis via Getty Images)

By the time Tyson was out of prison and had resumed his status as the top heavyweight in the world, Holyfield was brought to him as a sort of sacrificial lamb, another easy opponent to keep the Tyson cash flow going. At one time, Tyson-Holyfield was as big a fight as could be made in boxing. Now it was such a hard sell that cable providers were offering refunds if the fight lasted less than three rounds. The bout took place in November of 1996, a full five years after it was first canceled. Holyfield came in as a 5-1 underdog and won by 11th-round TKO. No one asked for a refund.

Tyson’s bout with Lennox Lewis also took a long time to materialize. A battle between the two had been suggested for years but seemed unlikely to happen when Lewis was KO’d by Hasim Rahman in April 2001. Lewis promptly KO’d Rahman in a return fight, and the wheels were immediately in motion for Lewis-Tyson. Both fighters were past their prime and vulnerable, so there was a sense that it had to happen before one or the other lost again. Moreover, Tyson’s behavior had become so strange that it seemed he’d self-destruct before the fight could be made.

Faster than you could say “emotional meltdown,” the January 2002 press conference to announce the fight saw Tyson attack Lewis and bite his leg. This resulted in another delay as Nevada refused to grant a license to the unpredictable Tyson. Several other states followed suit. The bout ended up at The Pyramid in Memphis, where Lewis stopped Tyson in eight. Lewis-Tyson set a new record for pay-per-view buys but left fans with a lingering question: Would the result have been different a few years earlier?

That same question haunted the Floyd Mayweather-Manny Pacquiao bout of May 2015, which may forever be the gold standard of delayed bouts. Had poet William Langland known of this bout, he never would’ve written the oft-quoted line about patience being a virtue. In fact, the most anticipated matchup in years, which Mayweather won by unanimous decision, was a stinker of the highest kind.

Mayweather-Pacquiao might be the finest example of a fight that waited too long. (Photo by Steve Marcus/ Reuters)

The fight was rumored to be signed as far back as 2009, but in the coming years it was delayed by endless disagreements over drug testing and disputes over money. Pacquiao’s 2012 losses to Tim Bradley and Juan Manual Marquez threatened to derail a bout with Mayweather once and for all. When the pair finally agreed to meet, the bloom was long gone from the rose, yet the fight was still an unprecedented financial success. But even as previous records for buy rates were toppling like dominos, fans were profoundly disappointed in the fight. Compounding the 12 rounds of tepid action was Pacquiao’s post-fight announcement that he’d fought with an injured shoulder. If this proverbial dead horse will allow us one more kick, Mayweather-Pacquiao was definitely not worth the wait.

Middleweight champion Marvelous Marvin Hagler wanted nothing more than a bout with Leonard. But he had to wait. And wait. And wait. Things seemed to be moving in the right direction in 1982, but Leonard retired, citing a recent eye injury and a loss of enthusiasm for the fight game. Hagler was stunned by the announcement and had to forge his career without Leonard’s help.

In 1984, Leonard staged a return that whetted Hagler’s appetite all over again. Unfortunately, Leonard looked so rusty in his comeback bout that he swiftly ducked back into retirement. Sensing Hagler was ripe for the plucking, Leonard returned to boxing in April of 1987 and beat Hagler by a close split decision. In a way, the Leonard-Hagler fight had been five years in the making. As in many other cases, the wait certainly helped at the box office, but one always wonders how things might’ve turned out had they fought in 1982.

What makes Crawford-Spence a bit different from the other bouts mentioned here is that neither fighter is a mainstream star. Of course, this isn’t their fault – society changes, and boxing’s place in it changes every few decades. Still, we’d be wrong to say this fight is bigger than boxing, which is what most of the other bouts mentioned here had in common.

But if it isn’t bigger than boxing, Crawford-Spence is certainly big in its own sweet way. For that reason, we should be glad it was made. Yes, it took a while. And it might’ve been different a few years ago. But you can’t deny that this one is juicy.

GET THE LATEST ISSUE AT

THE RING SHOP (CLICK HERE)

The cover of the June-July 2023 Summer Special was painted by Richard Slone.

[ad_2]

Source link