[ad_1]

Pre-order the limited edition Summer Special exclusively from the Ring Shop.

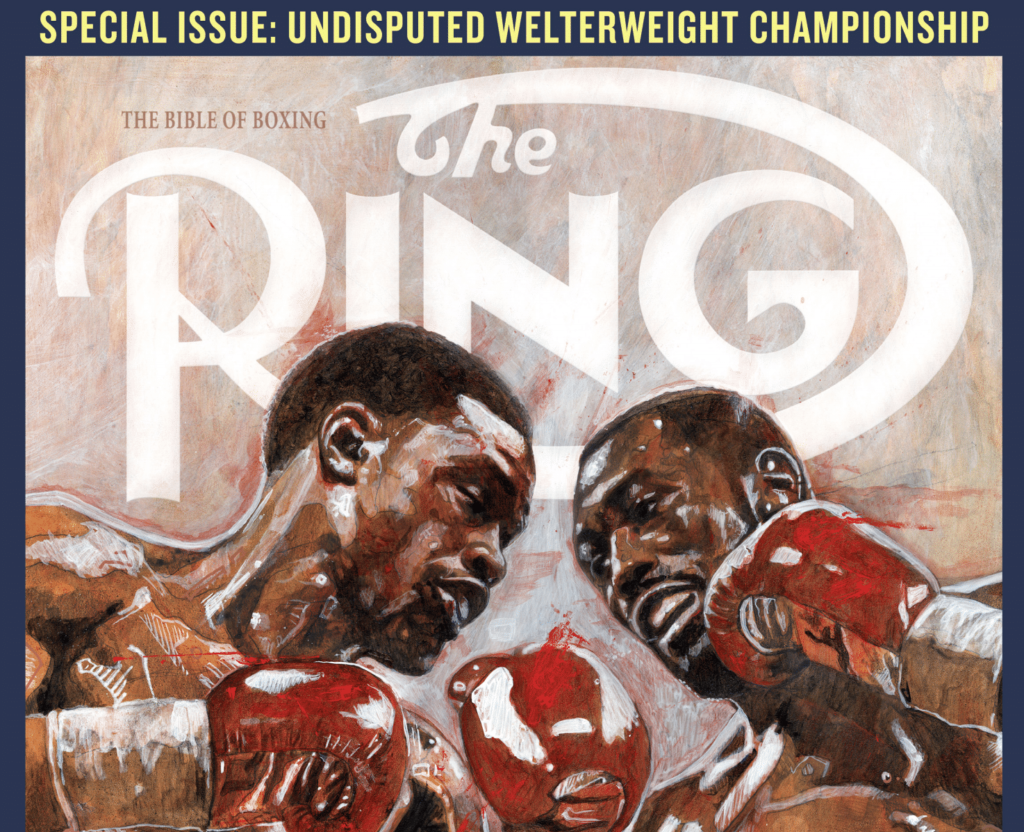

This essay by former Ring Magazine Editor-In-Chief Nigel Collins served as the cover story for the June/July issue of The Ring, which commemorated the Spence-Crawford showdown with a limited-edition print issue that is on sale now. Subscribers have digital access to the entire issue and 10 years of back issues.

PAST MEGA-EVENTS FEATURING WELTERWEIGHT STARS HAVE PRODUCED CLASSICS AS WELL AS DUDS. ARE SPENCE AND CRAWFORD UP TO THE TASK?

The best part of the Felix Trinidad-Oscar De La Hoya match was when De La Hoya’s promoter, Bob Arum, had one of his minions pull the plug on Don King’s microphone. The rival promoter was in his glory, a bellowing braggart, verbally twisting the knife. Arum was already steamed about the controversial majority decision in Trinidad’s favor and Oscar’s bewildering fade the final three rounds. Uncle Bob couldn’t change the result, but at least he knew how to shut up King. But even that stroke of magic couldn’t hide the fact that the fight had been underwhelming compared to all expectations, like your paycheck after taxes.

The “Tito” versus “Golden Boy” fight wasn’t quite a case of one boxer not wanting to fight and the other glad of it – but close. Two knockout artists refusing to trade punches is a sign of mutual respect, I guess, but not to the fans who pay the boxers’ wages. If they would have given it a go, it wouldn’t have mattered as much who won.

The task at hand is trying to figure out whether the upcoming Errol Spence Jr.-Terence Crawford match is going to be closer to the first Sugar Ray Leonard-Thomas Hearns match – one of the greatest welterweight title fights of all time – or the Trinidad-De La Hoya embarrassment.

Ever since Crawford moved up from junior welterweight to welterweight in 2018, boxing fans have been drooling over a match between Crawford and Spence. Negotiations dragged on and on for almost five years, so you couldn’t blame boxing’s beleaguered masses for figuring to hell with it, it’s never going to happen. Then, unexpectedly, the script flipped.

Barring further delay, Crawford and Spence will meet July 29 at the T-Mobile Arena in Las Vegas, televised by Showtime PPV. The winner will be undisputed welterweight champion, covered in layers of belts, including The Ring’s, and looking a bit like an upright armadillo with a big smile on its face. Nonetheless, the belts are secondary to what the public wanted all along, a violent confrontation between two of the best boxers in the word who just happen to be 147-pounders.

Like Spence and Crawford, Oscar De La Hoya and Felix Trinidad were undefeated welterweight champs ranked in the pound-for-pound top five when they fought in 1999. (Photo By Jose Jimenez/Primera Hora/Getty Images)

Spence-Crawford is the kind of match that promises much, but there are no guarantees. The best vs. the best does not always make the best fights. Nonetheless, when they do, marvelous things happen – boxing rises above its outlaw birthright and reminds us why we care. Putting aside the possibility of another impediment, we have a reasonably good chance of a splendid fight. Between them, Crawford and Spence are undefeated in 67 pro fights and have 52 knockouts. But numbers don’t win fights, fighters do.

Floyd Mayweather’s 12-round decision over Manny Pacquiao was the biggest money fight in boxing’s history and it stunk like a dead rat in the wall. There were no knockdowns, no highlights, no meaningful exchanges, and neither was ever in danger of getting hurt. What did get hurt, and hurt badly, was the sport itself. Hundreds of millions of dollars were spent on a glorified sparring session. Any lackluster fight sucks, but when it happens at the highest level there are consequences beyond the ring. Many new customers, caught up in the hype, were probably asking themselves, “Is that all there is?”

Crawford and Spence are as good as it gets these days and have an opportunity to compensate for the disappointing PPVs and superfights we’ve endured. Their skillsets are off the chart, their records pristine. As far as we know, they can do just about anything in the ring, so there’s little gained by dissecting physical attributes. How their bodies perform on the night will play out in plain sight, but whatever is in their hearts and minds will go a long way toward what happens when the bell rings.

Crawford is known for being a technician with vicious finishing power. (Photo by Ed Zurga/Getty Images)

“Bud” Crawford once tweeted, “I fight so hard because I’ve been scared since a child.” For a skinny little kid living in a dangerous part of Omaha with a father away in the military, fighting was mandatory. He might have been scared, but Bud got good at it. Real good.

Crawford is reminiscent of Bernard Hopkins, and like B-Hop, the 35-year-old Crawford has become the consummate pro, understanding the nuances of the sweet science, using his boxing IQ as much as his fists. The Nebraskan is quick and purposeful on his feet, fast with his hands and can end a fight quickly. Mid-fight adjustments? No problem. He’s like a geometrician in the ring, and once he’s figured out the correct angle of attack, he goes to work.

He’ll be facing a slightly younger man in the 33-year-old Spence, a guy who has bounced back from flipping his Ferrari 488 Spider multiple times. Spence was saved because he wasn’t wearing a seatbelt and was therefore tossed from the car. He posted on social media that he felt “like Superman.” Whether it was luck, fate or the absence of Kryptonite, the only real physical damage was to Errol’s face. When the plastic and dental surgeons were done, the only difference was that he looked a little bit more like a fighter. That’s all. An incredible escape from certain death.

After his car crash, Spence made a profound lifestyle change by purchasing a 60-acre ranch in DeSoto, Texas, south of Dallas. “I really can’t tell you why I bought [the ranch],” Spence told writer Bob Velin. “Once I did, I started buying horses and I bought more cattle and fixed the place up. It gave me peace of mind after living downtown. And the serenity of being here in my backyard … nobody bothered me. It’s a beautiful thing after being in a high-rise.

“I was just trying to find answers, you know. I needed to go somewhere new and start over and get out of the dark cloud that was downtown and be in a better place, because I’m already like an introvert.”

“This is definitely a legacy fight.”

– Errol Spence Jr.

A video of the champ grooming one of his horses, decked out in colorful shorts, rubber boots and a green baseball cap pretty much sums up life at the ranch, where he lives with his children. Boxing’s version of Green Acres, minus Arnold Ziffel.

There is, however, nothing bucolic about his fighting style. Spence likes to move in behind his southpaw jab, throw a left to the body and then a left to the head, or maybe a pair of left uppercuts. He applies pressure relentlessly, working hard to break down his man. But staying in the pocket too long can be dangerous, as Spence discovered in an April 2022 welterweight unification bout with Yordenis Ugas.

Spence’s laid-back demeanor outside the ring belies the danger his opponents face. (Photo by Nigel Roddis/Getty Images)

In the sixth round, Ugas sent Spence flying halfway across the ring and into the ropes with a terrific right to the head. The Texan bounced off the ropes like a WWE wrestler and back into the fray. Ugas’ only chance of victory had passed, and Spence pounded the Cuban’s right eye shut and the fight was stopped at 1:44 of the tenth round.

Crawford is unlikely to put himself in position to be hit anywhere near as frequently as Ugas was by Spence, but Bud was rocked by his most recent opponent, David Avanesyan, prior to knocking out the Russia-born Armenian in the sixth round. Neither Spence nor Crawford has been knocked down as a pro, but the Ugas and Avanesyan incidents proved they’re not invulnerable.

Spence and Crawford will each be fighting the best adversary of their professional career. This can spook even the finest boxers, as I believe it did when Trinidad fought De La Hoya. This is not to say they were afraid of each other; I believe they were subconsciously worried about losing their undefeated records and superstar status. It made them both more wary than usual.

The antidotes for half-stepping when faced with a formidable challenge are self-belief and pride. That sounds obvious, corny even, but the bravest among us have doubts, and it takes awe-inspiring faith in your ability to conquer fear and go for broke against a daunting foe. It’s easier to play it safe. You know, jab and move, jab and move, clinch, repeat, etc.

Despite sterling careers, neither Spence nor Crawford has had a signature fight, the one people will automatically associate with their names for years to come, their magnum opus perhaps. Win a signature fight and the boxer is liable to turn up on a late-night talk show, always a sign the fighter is nibbling at the edge of mainstream acceptance. Crawford vs. Spence has a decent shot at delivering that kind of fight, yet another motive for an audacious approach.

Combatants’ prefight quotes are usually quickly forgotten, except when the winner reminds us, “I told you so.” But early statements from Spence and Crawford were encouraging. “Our fight will be the most anticipated, action-packed fight in the past 30, 40 years,” Spence said. “This is definitely a legacy fight.”

“The fight will sell itself, because everybody knows what they’re getting on fight night,” Crawford said.

That depends on which “everybody” he’s referring to. Yes, the hardcore boxing fans can hardly wait for the first bell to ring. There will be some newbies and casuals, too, but their numbers probably won’t be as high as those that helped turn the Gervonta Davis-Ryan Garcia match into a financial bonanza.

“The fight will sell itself, because everybody knows what they’re getting on fight night.”

– Terence Crawford

Fair or not, at this point Davis and Garcia are more widely known and popular than Spence and Crawford, even though the latter have better resumes. Davis and Garcia turned out to be a one-sided fight, but the announced pay-per-view buys (1.2 million) and live gate at Vegas’ T-Mobile Arena ($22.8 million) were already in the bank by the time Davis eviscerated Garcia with a left to the body in the seventh round.

The personality gap can make a significant difference. Davis is boxing’s new bad boy and Garcia its latest heartthrob, which made them more marketable, but not necessarily better fighters. Spence and Crawford are just not as charismatic as Davis and Garcia, but an exceptional fight on July 29 would change that equation and elevate Errol and Bud in the minds of the paying public. Neither Marvin Hagler nor Thomas Hearns was particularly charismatic outside of the ring, but the dynamic fashion in which they fought superseded their personas.

(Photo by Esther Lin/Showtime)

Crawford is strictly business, a serious student of the game dedicated to his craft. “I’m a fan of the sport,” he said. “A lot of times, I get to the fights real early and watch all the fights. I also like to see the top fighters in the world, see how they break down their opponents, what they do in certain circumstances. I look for anything where I can get an edge.”

Without a shred of evidence of eroding skills, there have been concerns raised about the age difference, the lengthy layoff both have endured and the possibility that Crawford is starting to feel the weight of a longish career. While it’s often said that a boxer can grow old virtually overnight, there is usually some foreshadowing that occurs, some hint that he or she is beginning to decline. Crawford’s recent performances indicate he’s still in his prime and capable of winning the fight, as is Spence, who isn’t all that much younger.

According to FanDuel, there is no favorite; both boxers are -112/-112 or -110/-110.

“As the fight gets closer, the odds will probably move a little bit, but I’m guessing they won’t move a lot,” said Eric Raskin, longtime boxing journalist and writer/editor for USBets.com. “I would be surprised if either guy gets priced more than a -150 favorite.”

There are no wagers on whether a fight is going to be exciting or boring. That’s entirely up to the matchmakers and participants. He wasn’t writing about boxing, per se, but Bob Goff once wrote, “Most stories don’t have the ending we would give them right away. The better endings come late.” This might be one of them.

Spence and Crawford know it’s a major chance to create a signature fight, raise their marketability and prove the boxing industry can produce a PPV worthy of being called a super fight.

THE BEST AND THE WORST 147-POUND TITLE BOUTS

Ever since Boston’s Paddy Duffy became the first welterweight champion of the gloved era (skin-tight gloves) by knocking out Billy McMillian on October 30, 1888, the division has been a popular mainstay of boxing. Here, in chronological order, are five samples of the greatest welterweight fights and five of the worst.

THE STANDOUTS

McLarnin and Ross weigh in. (Photo by KEYSTONE-FRANCE/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

Jimmy McLarnin SD 15 Barney Ross, September 17, 1934

Four months earlier, Ross had defended the welter title with a split decision over McLarnin in front of around 60,000 fans at the Madison Square Garden Bowl in Long Island. When they fought again at the same venue, the Associated Press described it as “a dazzling duel that shifted first in one direction and then the other, then back and forth again through the entire 15 bristling rounds.” Even though lots of fans thought Ross should have gotten the decision, it was selected by The Ring as Fight of the Year. Ross regained the title with a 15-round unanimous decision in 1935.

Carmen Basilio KO 12 Tony DeMarco, November 30, 1955

Basilio had taken DeMarco’s welterweight championship in June, but it was a good fight, so they did it again. DeMarco did much better in the rematch. He was outpunching the champ and leading 79-74, 78-67 and 79-73 after eight rounds. Then things changed. “Suddenly, DeMarco looked like he was fighting in slow motion as Basilio continued to work the body in the tenth,” wrote Bert Sugar. An exhausted DeMarco was down twice in the eleventh, and referee Mel Manning stopped the fight to save the helpless boxer, who was hung up on the ropes. It was The Ring’s 1955 Fight of the Year

Roberto Duran UD 15 Sugar Ray Leonard, June 20, 1980

Leonard, the WBC welterweight titleholder, was 27-0 with 18 KOs, while Duran was 71-1 with 56 KOs, a vast experience advantage. However, Leonard was a 9 to 5 favorite. The fight was held at Olympic Stadium in Montreal, the same venue where Leonard won an Olympic gold medal in 1976. The attendance was 46,317. “It was, from almost the opening salvo, a fight that belonged to Duran,” wrote Bill Nack for Sport Illustrated. “The Panamanian seized the evening and gave it what shape and momentum it had.” Although Duran deserved the decision, it wasn’t the one-sided fight Nack’s report indicated. Leonard fought back and had his share of moments.

Duran vs. Leonard. (Photo by Manny Millan /Sports Illustrated via Getty Images)

Shane Mosley SD 12 Oscar De La Hoya, June 17, 2000

From the start, it was a passionate struggle between two magnificently conditioned athletes at the peak of their powers. The Staples Center was full to the brim with the 20,744 fans who got their money’s worth regardless of which boxer they were rooting for. De La Hoya’s best rounds were the fifth and sixth, when he momentarily slowed Mosley with left hooks to the body during several intense exchanges. Sugar Shane zapped Oscar with laser-like lefts and rights, darting in and out, shifting from side to side, but never running. Officially, at least, Mosley needed the 12th round to win the fight. Nothing was held back in the punch-filled finale. De La Hoya never stopped trying, never stopped letting his hands go, but Mosley outlanded “The Golden Boy” by an incredible 45 to 18 margin to win a split decision.

Simon Brown KO 10 Maurice Blocker, March 18, 1991

Brown was 13 when he and his pal Blocker emigrated from Jamaica. They settled in the Washington, D.C., area and had their first pro fights on the same card in Atlantic City. Brown won the vacant IBF welterweight title on April 23, 1988, with a 14th-round knockout of Tyrone Trice. On August 19, 1990, Blocker won a 12-round majority decision over Marlon Starling to annex the WBC welterweight belt. It seemed inevitable that the pair would eventually clash in a unification bout, and they did in Las Vegas on March 18, 1919. It was a suspenseful thriller. At 6-foot-2, Blocker had a five-inch advantage over the 5-foot-9 Brown and used his superior height and reach to keep Simon on the outside much of the time. Maurice was slightly ahead when Brown nailed him with a right hand and a whistling left hook in the tenth round. Both blows landed flush on the head, and Blocker went down hard. There wasn’t a count. It was obvious Blocker was in no condition to continue, and Referee Mills Lane stopped the fight.

Brown (right) did not let friendship get in the way of victory. (Photo: The Ring Magazine)

THE STINKERS

Joe Walcott WDQ 10 Mysterious Billy Smith, September 24, 1900

Walcott and Smith had a six-fight series between 1895 and 1903. Walcott won the series 3-1-2, but it was never easy fighting the man known as “The Dirtiest Fighter Who Ever Lived.” The match was held at the Charter Athletic Club in Hartford, Connecticut. According to Nat Fleischer, it was “a battle in which foul tactics prevailed.” Apparently, Smith’s were more egregious than Walcott’s, because referee Johnny White disqualified him in the tenth round.

Johnny Saxton UD 15 Kid Gavilan, October 20, 1954

Both Saxton and Gavilan were connected to mobsters Frankie Carbo and Blinky Palermo. The fight, held at Philadelphia’s Convention Hall, is generally considered a fix. Saxton was an unpopular jab-and-grab boxer, while Gavilan was a flashy showman who was so popular that he was on national TV 34 times. Saxton refused to make an offensive move; he just clinched whenever Gavilan advanced. Insiders, including the press, knew beforehand that the fight wasn’t on the level. Gavilan also benefited from the mob’s devious methods, especially in his August 29, 1951, title defense against Billy Graham. When Gavilan won a 15-round split decision, the Madison Square Garden crowd erupted in a violent protest.

Gavilan’s loss to Saxton (right) may not have been on the up and up. (Photo: Getty Images)

Sugar Ray Leonard KO 8 Roberto Duran, November 25, 1980

Six months after their first fight, Leonard and Duran fought the scandalous “No Mas” rematch in New Orleans. Leonard was ahead on all cards after seven rounds by scores of 67-66, 68-66 and 68-66, and though he didn’t have an insurmountable lead, Sugar Ray was looking sharp. He was using his legs and hand speed to outbox “Manos de Piedra” and at times making him look foolish. Suddenly, Duran turned away from Ray, gestured with his hand and, according to common lore, uttered two words that will live forever in boxing infamy. There are many theories as to why Duran quit in the eighth round when he wasn’t hurt, but none of them persuasive enough to justify his actions.

Pernell Whitaker D 12 Julio Cesar Chavez, September 10, 1993

Going in, Chavez was No. 1 in The Ring’s pound-for-pound ratings and Whitaker was No. 2. Their styles were totally different. Chavez was a pressure fighter with a big punch, while southpaw Whitaker was a defensive genius and crisp counterpuncher. They fought in San Antonio at a catchweight of 145 pounds. Except for the fifth round, when Chavez connected well to the body and head, Whitaker was in charge, controlling the fight as Chavez grew progressively frustrated with Pernell’s elusive style. When a draw verdict was announced, even some of the pro-Mexican fans booed. The outrageous decision is considered one of the worst in boxing history.

Oscar De La Hoya KO 3 Patrick Charpentier, June 13, 1998

Every now and then, a great event has a disappointing fight. Such was the case when De La Hoya fought (if that’s the correct word) French challenger Charpentier. El Paso had fight fever, and it was a fun week with plenty of prefight events to attend. It seemed like every local we met was talking about the fight. The French challenger didn’t stand a chance, but a crowd of 45,329 turned up at the Sun Bowl anyway. At least half of them were women infatuated by Oscar. “The Golden Boy” knocked Charpentier down three times in the third round, ending the bout at the 1:56 mark.

GET THE LATEST ISSUE AT

THE RING SHOP (CLICK HERE)

The cover of the June-July 2023 Summer Special was painted by Richard Slone.

[ad_2]

Source link